Elderly Couple Mocked for Building a Second Wall Around Their Tiny Cabin – Until It Stayed 41° Warmer

He let her go, watching her disappear into the crowd of people who needed her. And he understood suddenly what had been killing them both all these years.

It was not the cold, not the poverty, not the aching joints or the failing bodies. It was loneliness.

They’d been dying of loneliness, and they hadn’t even known it. The first crisis came around 2:00 in the morning.

Harold had been dozing in his chair when a commotion near the door jerked him awake. A man was trying to leave—one of the younger ones, maybe 30, with a wife and two small children huddled in the corner.

“I have to check on the house,” the man was saying, struggling against the hands trying to hold him back. “The pipes… if the pipes freeze…” “Your pipes are already frozen,” Carl Hendris said, his voice rough but firm. “They froze 12 hours ago, same as everyone else’s.” “But my tools, my equipment… everything we own is in that house!” “And it’ll still be there when this breaks. But you won’t be if you go out in this.”

The man—Harold thought his name might be Peters, one of the families that had moved to Ridge Creek a few years back—looked around wildly. His eyes were too bright and his movements too jerky.

Harold recognized the signs. It was panic, the kind that came when a man felt helpless and couldn’t stand it.

Harold pushed himself up from his chair and made his way through the crowd.

“Son,” he said quietly, putting a hand on Peters’ shoulder. “What’s your name?” “David.” “David Peters?” David nodded jerkily. “David, look at me.”

Harold waited until the younger man’s frantic eyes focused on his face.

“I know what you’re feeling right now. I know you want to do something. Fix something. Make it right. That’s what men do when their families are in danger.”

David nodded jerkily.

“But the bravest thing you can do right now is nothing. Stay here. Keep your wife warm. Let your children sleep without seeing their father walk out into the cold and not come back.”

Harold squeezed his shoulder.

“Your house will wait. Your family needs you now.”

The fight went out of David Peters like air from a punctured tire. His shoulders slumped, and when he turned back toward his family, Harold saw the tears he was trying to hide.

Mabel appeared at Harold’s elbow with a cup of tea. She pressed it into David’s hands without a word, then guided him back to his wife and children.

“That was good,” Carl said quietly, coming to stand beside Harold. “What you said to him.” Harold shrugged. “Said what needed saying.” “How do you know how to stay calm? I mean, when everything’s falling apart?”

Harold considered the question. Outside, the wind had picked up again, screaming around the corners of the cabin with renewed fury.

The outer wall groaned slightly—the first sound it had made all night—and Harold felt a flicker of concern before the groaning stopped.

“Experience, I suppose,” he said finally. “You live long enough, you learn that panic doesn’t help anything. The cold doesn’t care if you’re scared. It just does what it does. All you can control is yourself.”

Carl was quiet for a moment. “I’ve been a fool, Jensen.” “We’ve all been fools at one time or another.” “No, I mean…”

Carl struggled with the words. “I looked at you and Mabel and all I saw was two old people who should have given up years ago. I didn’t see…”

He gestured around the cabin. “I didn’t see this. What you built. Who you are.”

Harold didn’t know what to say to that, so he said nothing. They stood together in silence—two men who had been something like enemies for 20 years—watching the cabin full of people who were surviving because one of them had refused to quit.

The second crisis came at 4:00 in the morning. A child—a little girl, maybe six years old—woke up crying that she couldn’t breathe.

Her mother’s screams cut through the crowded cabin like a knife. Suddenly everyone was awake, everyone was moving, and Harold felt the old familiar fear clenching at his chest.

Dr. Sarah Chen pushed through the crowd; Harold hadn’t even known she was there. She was a physician from the clinic in town who must have come with one of the later groups.

She knelt beside the little girl and began her examination with calm, professional movements.

“Asthma attack,” she announced after a moment. “Does anyone have an inhaler? Any kind of bronchodilator?”

Silence. In the rush to escape their freezing homes, people had grabbed children and blankets and whatever food was closest.

Medical supplies hadn’t made the list.

“I have,” a woman’s voice came from near the back. “I have an old inhaler. It’s expired, but…” “Get it.”

The expired inhaler helped, but not enough. The little girl—her name was Emma, Harold learned later—was still wheezing, still struggling.

Her lips were taking on a bluish tinge that made Harold’s stomach clench.

“She needs a nebulizer,” Doctor Chen said, her voice tight. “Or steroids. Something to open her airways.” “There’s nothing!” Emma’s mother sobbed. “There’s nothing here!”

Harold’s mind raced through the contents of his cabin: decades of accumulated supplies, tools, remedies. There had to be something.

Then he remembered. “Mabel!” he called out. “The cabinet above the sink. The jar with the dried leaves.”

Mabel found it and brought it over. Doctor Chen looked at the jar skeptically.

“Mullein?” Harold explained. “My grandmother used it for chest complaints. You steep it in boiling water and breathe the steam.” “That’s folk medicine.” “It’s what we have.”

Doctor Chen hesitated for only a moment. Then she nodded. “Get me boiling water and a towel to make a tent over her head.”

They worked together: the physician and the old man with his grandmother’s remedies. Mabel brought the kettle and Harold showed Doctor Chen how to prepare the Mullein the way his grandmother had taught him 60 years ago.

They made a tent over Emma’s head with a blanket and let her breathe the medicated steam. It wasn’t a miracle; the little girl didn’t suddenly bounce up fully healed, but her breathing eased.

The blue tinge faded from her lips, and when she finally fell asleep in her mother’s arms, her chest rose and fell with something approaching normalcy.

“Where did you learn that?” Dr. Chen asked Harold afterward, washing her hands in water that Mabel had heated on the stove. “My grandmother. She was a healer in the old way. Herbs and roots and things people have forgotten. She came over from Norway when she was 16. Brought all that knowledge with her.” “The double wall, the Mullein… it’s all from the same source?”

Harold nodded. “Old ways. Things people figured out over centuries because they had to. Modern life made us forget.”

Dr. Chen looked around the cabin at the walls that were keeping them all alive and at the jar of dried leaves that had helped a little girl breathe.

“Maybe we shouldn’t have forgotten,” she said.

The night crawled toward dawn. Harold moved through the cabin in slow circuits, checking on people, checking on the walls, and checking on the fire that Mabel kept burning with the steady expertise of a woman who had been keeping fires alive for 50 years.

The outer wall continued to hold, absorbing the worst of the cold and protecting them all with the simple physics of dead air, hay, and moss. Around 5:00 in the morning, the wind dropped suddenly.

The silence was almost shocking after hours of constant howling. Harold went to the window and looked out.

The sky was still dark, but there was a quality to the darkness that suggested dawn wasn’t far off. The aurora had faded, replaced by a scatter of stars that seemed to pulse with cold light.

The thermometer outside read 58 below zero. 58 below.

Harold had lived in Alaska for half a century, and he’d never seen it that cold. That was the kind of temperature that killed car batteries in minutes, turned exposed skin to frostbite in seconds, and could crack trees like gunshots as the sap froze and expanded.

And inside his cabin, surrounded by 31 other people, it was 41 degrees warmer.

“Harold.” Mabel’s voice came from behind him. “Look.”

He turned. She was pointing at something near the far wall, a spot where the wallpaper had peeled away years ago, exposing the bare logs beneath.

Normally in cold like this, those logs would be rimmed with frost on the inside, weeping moisture that froze as soon as it touched the wood. But the logs were dry.

They were completely dry. The double wall was working so well that the cold wasn’t even reaching the original structure anymore.

“I’ll be damned,” Harold whispered. “I’d rather you weren’t,” Mabel said, smiling. “We’ve got too much to do.”

Dawn came slowly, the way it always did in December—a gradual lightening of the sky from black to gray to the pale blue of a winter morning. People stirred, stretched, and began to remember where they were and why.

The temperature outside hadn’t changed—58 below zero according to the radio—but the sun was rising and there was something about daylight that made even the worst situations feel more manageable. Martha Dalton was one of the first to fully wake.

She sat up, looked around the crowded cabin, and seemed to see it clearly for the first time.

“Harold,” she said. “How are you feeding all these people?”

It was a good question. Harold and Mabel had stocked up before the cold snap, but their supplies were meant for two people, not 32.

They’d been stretching everything—the tea, the soup, the bread—but there was a limit to how far things could stretch.

“We’re managing,” Harold said. “That’s not what I asked.”

Before Harold could respond, Carl Hendris spoke up from across the room.

“I’ve got canned goods in my truck. Brought them when we came. Figured they’d be safer here than in my freezing house. Beans, corn, some soup.” “I have bread,” said another voice, Linda Morrison. “Two loaves plus some cheese.” “There’s meat in my cooler,” someone else offered. “Moose steaks. They’ll be frozen solid, but we can thaw them on the stove.”

Within minutes, people were pulling supplies from pockets, bags, and truck beds—food they’d grabbed without thinking, provisions they’d almost forgotten they had. Mabel organized it all with quiet efficiency, creating an inventory, planning meals, and making sure nothing was wasted.

“We’ve got enough for two days,” she announced. “Maybe three if we’re careful.”

“The cold snap’s supposed to break tomorrow night,” Doctor Chen said, checking her phone. “Cell service is spotty, but I got a forecast through. Temperatures rising to 15 below by Wednesday.”

15 below. A week ago, that would have sounded miserable; now it sounded like a heatwave.

The day passed in a strange kind of rhythm. People took turns sleeping, eating, and using the outhouse that Harold had built years ago and that was now serving more people in a day than it usually served in a month.

Children played quiet games in corners, supervised by whoever happened to be awake. Adults talked in low voices, sharing stories and comparing notes on the damage they’d fled.

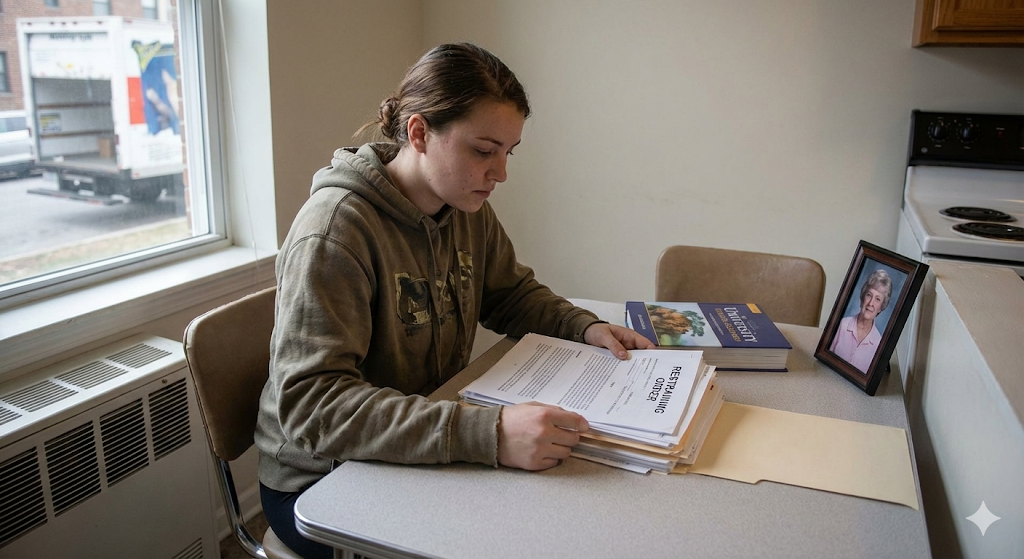

Harold spent most of the day answering questions about the double wall.

“How far out from the original structure?” Ray Morrison wanted to know, taking notes on a piece of cardboard. “About 8 inches. Far enough to create a good air gap, close enough to build easily.” “And the insulation?” “It has to be dry. Hay works. So does moss, dry leaves, straw, even crumpled newspaper. Anything that traps air. The key is making sure it’s dry. Wet insulation doesn’t insulate; it conducts cold.”

“What about vents? You mentioned vents.” “Small ones near the top of the wall. You need some air circulation or you get moisture buildup, and moisture leads to rot. But they should be small—just big enough to prevent condensation, not big enough to let cold air in.”

He drew diagrams on the backs of envelopes. He sketched designs on people’s hands when they ran out of paper.

He explained the physics over and over again. How air was actually a good insulator when you kept it from moving, how the enemy wasn’t cold itself but heat loss, and how a barrier didn’t have to be thick to be effective if it was designed right.

“You should write this down,” Dr. Chen said, watching him explain the concept to a group of younger men. “Make it official. A guide that people could follow.” “I’m not a writer.” “You don’t have to be. Just write what you know, what you’ve taught us today. That could save lives.”