[FULL STORY] What’s the worst part about being the “responsible” sibling?

Parallel Dimensions

Dr. Kumar, Riverside’s lead psychiatrist, identified specific markers of delusional disorder with complicated grief.

She explained how Mikey’s brain had created an alternate reality to cope with unbearable loss. The clinical explanation helped me understand this wasn’t a choice; his mind had fractured under the weight of trauma.

Mikey’s recorded therapy sessions at Riverside revealed the elaborate internal world he’d constructed. Dr. Kumar played the recordings for me during a treatment planning meeting.

In his mind, Alice lived in a parallel dimension accessible only through specific rituals.

He described her daily routines there, the conversations they had, and the meals they shared. The detail was staggering.

He’d created an entire life for her, complete with friends, hobbies, and adventures that never happened.

The treatment notes validated every incident I’d documented over the past two years.

Each manipulation tactic, each escalation, and each delusional episode matched the patterns Dr. Kumar had seen in similar cases.

The validation felt hollow, though. Being right meant accepting how sick my brother truly was.

A court-appointed advocate reviewed Mikey’s case file, interviewing staff members and reviewing the extensive documentation.

Her recommendation came swiftly: extended involuntary commitment with regular reassessments. The legal framework would ensure Mikey couldn’t simply charm his way out again.

The New Proxy

Riverside’s treatment team, my extended family members who’d finally understood, and the medical professionals all agreed on a six-month minimum program.

The consensus felt like progress, but I knew six months was just the beginning. Recovery from delusions this deep could take years, if it happened at all.

Then Mikey found a new proxy.

Another patient at Riverside dealing with his own reality distortions began calling my workplace repeatedly.

He claimed to be Alice’s friend with an urgent message about her safety. My employer’s patience wore thin as the calls disrupted business operations.

The receptionist started screening all calls, but they kept coming from different numbers. My boss pulled me into his office again.

The company had been supportive, but the harassment was affecting other employees now. He mentioned the possibility of a restraining order against the facility if the calls didn’t stop.

I understood his position but felt trapped between protecting my job and ensuring Mikey got treatment.

Accusations from Afar

That evening I finally received an email from my parents. It was not the supportive message I’d hoped for but a terse accusation.

They blamed me for not managing Mikey better and for letting his grief spiral out of control.

They’d been gone for over a year, refusing to engage with his illness, but somehow this was my failure. The unfairness of it burned.

The placement hearing arrived faster than expected. Emma had a work crisis she couldn’t avoid—a system failure that required her immediate attention.

I sat alone in the conference room at Riverside, presenting Mikey’s case to the review board. My voice stayed steady as I detailed the manipulation, the escapes, and the danger he posed to himself and others.

During a break, I made a decision that had been building for weeks: I would pursue legal guardianship of Mikey.

Our parents had abdicated their responsibility, and someone needed to make medical decisions for him.

The process would be complicated, expensive, and almost certainly contested by our parents if they found out.

Word of my guardianship plans reached Mikey through the facility grapevine. His reaction was immediate and violent.

He threw a chair during group therapy, screaming about betrayal and imprisonment. It took three orderlies to restrain him.

The medication adjustment that followed left him sedated for days, but the medical team assured me it was necessary for everyone’s safety.

The Confrontation

My phone rang at dawn three days later. The facility had contacted our parents as emergency contacts after Mikey’s outburst.

They were driving down demanding his immediate release to their custody. They hadn’t seen him in over a year and hadn’t witnessed his delusions, but they were convinced they could pray his illness away.

The family meeting that afternoon erupted within minutes.

I spread two years of documentation across the conference table while our parents insisted we just needed to reconcile as brothers.

“Boys will be boys.” Mom kept saying.

“Grief made people do strange things.” she said.

Dad suggested I was being dramatic and that Mikey just needed to come home and rest. Then Mikey revealed something that shattered their denial.

He’d been calling Alice’s old cell phone number every night. Our parents had kept paying the bill, unable to let go of that last connection.

Mikey described the voicemails he left—detailed conversations with Alice about her life in the other dimension. Mom’s face went white as she realized she’d been enabling his delusions.

Dr. Kumar intervened when Dad suggested prayer therapy and herbal remedies. She explained the neurological basis of Mikey’s condition and the structural changes grief and psychosis had created in his brain.

Her professional authority carried weight even with my skeptical parents. She made it clear that without proper treatment Mikey would likely attempt another grave excavation or worse.

A Fragile Agreement

I faced a choice: fight my parents in court for guardianship, likely destroying what remained of our family, or find a compromise that ensured Mikey’s treatment.

The legal battle would be expensive, time-consuming, and traumatic for everyone. But Mikey needed consistent, long-term care that our parents’ denial might interrupt.

After hours of negotiation, we reached an agreement. Our parents could visit Mikey under supervision if they attended family therapy sessions and supported the treatment plan.

They would share the financial burden of his care, which eased my depleted savings. Most importantly, they wouldn’t interfere with medical decisions.

The first supervised visit tested everyone’s resolve. Mikey had prepared an elaborate birthday party for Alice in the common room, complete with a cake he’d convinced another patient to help him make.

When staff tried to redirect him, he melted down completely, accusing our parents of missing Alice’s special day.

Mom sobbed as she watched her son sing happy birthday to an empty chair.

Mikey’s attempt to manipulate our parents followed his established pattern. He called Mom by Alice’s name, begged her to take him home so they could be together.

The manipulation might have worked a year ago, but watching him in full delusion broke through their denial.

Dad had to leave the room when Mikey described how our parents had neglected Alice, projecting his own guilt onto them.

Breaking the Denial

The crack in their denial widened during family therapy. Mikey accused them of abandoning Alice, of loving me more, and of causing her death through their favoritism.

None of it was true; our parents had loved all three of us equally. But Mikey’s fractured mind needed someone to blame, and he’d expanded his target list beyond just me.

With our parents finally accepting the reality of Mikey’s illness, we secured funding for his extended treatment.

Their insurance combined with mine would cover a full year at Riverside, with options for continued care if needed.

The financial relief was significant, but more important was having family unity in supporting Mikey’s treatment.

Something shifted in Mikey after our parents committed to family therapy. He began cooperating with medication trials, though he still insisted Alice visited him at night.

The new antipsychotic reduced his agitation and made him more receptive to reality orientation exercises. Progress was slow, measured in tiny increments, but it was progress.

I spent a weekend going through Alice’s belongings in storage. Emma helped me sort through clothes, books, and keepsakes.

We donated most items to charity, keeping only a few meaningful pieces. The process felt like another goodbye, but a necessary one.

Holding on to her physical possessions wouldn’t bring her back, and Mikey’s fixation on her belongings had fueled his delusions.

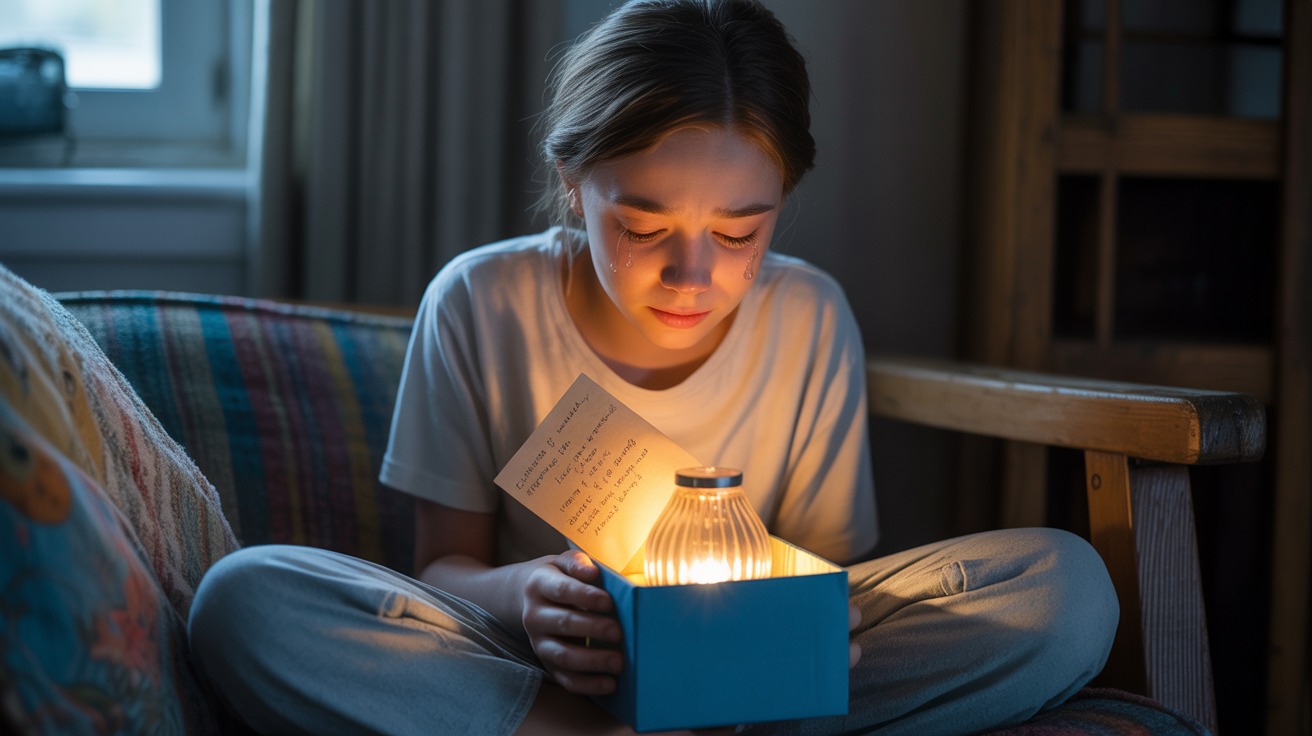

A Moment of Clarity

Three months into the new treatment protocol, during a family session, Mikey said something that stopped everyone cold.

He looked at the empty chair where he usually placed Alice’s imaginary presence and whispered that she wasn’t coming.

Dr. Kumar gently asked what he meant. Mikey’s eyes filled with tears.

He said Alice was gone and had been gone since the accident. It was the first time he’d acknowledged her death as real.

The breakthrough didn’t last. By the next session, Mikey was back to describing Alice’s parallel world.

But that moment of clarity gave us hope. Dr. Kumar explained that recovery from delusions wasn’t linear.

There would be setbacks, returns to fantasy, and moments of confusion. But acknowledgment, even brief, meant the medication and therapy were creating cracks in his alternate reality.

I established a routine of weekly visits, always during structured activity times. Boundaries were essential: no discussing Alice’s whereabouts, no feeding into delusions, and no bringing items he might incorporate into fantasies.

Some visits went well, with Mikey seeming almost like his old self. Others ended with him accusing me of hiding Alice or demanding I admit to crimes I hadn’t committed.

Lala

One year later, I stood at Alice’s grave with Emma, our parents, and Mikey. He was on a day pass, heavily medicated but stable.

The cemetery looked different in daylight than during his midnight excavation attempt. Mikey placed fresh flowers on the headstone, his hands shaking slightly from medication side effects.

He looked at the grave for a long moment then said the words we’d waited so long to hear.

He missed his sister, Lala.

He missed not the elaborate fantasy he’d created, but the real girl who died on a highway two years ago.

Our family was broken and would always be broken, but we were learning to tend our wounds with professional help, proper boundaries, and the understanding that some grief is too large for the human mind to hold.

I’d fought for both my siblings in different ways: one I couldn’t save, and one I could only help contain.

Standing there together, damaged but present, felt like the only resolution our story could have.