“He Is Dangerous” — My Father Said about our Neighbor, I Acted like a Naive Girl and…

I put some into an emergency fund and used the rest for a down payment on a house. A small house, nothing fancy; just three bedrooms and a nice yard.

The house was right next door to Theodore Ashford. My real estate agent thought I was crazy.

Why would a young woman want to live next to an elderly professor in a quiet neighborhood? I didn’t explain; some things are too complicated for real estate transactions.

I quit my job at the accounting firm. Eight years of fluorescent lights and dying coffee machines were enough.

I started my own bookkeeping business, working with small businesses and independent contractors who needed someone to keep their finances straight. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was mine.

My name on the door, my rules, my life. Theodore and I had dinner together every Sunday.

He would cook his mother’s recipes—the ones Eleanor had never gotten to teach me. I would bring dessert from the Italian bakery downtown.

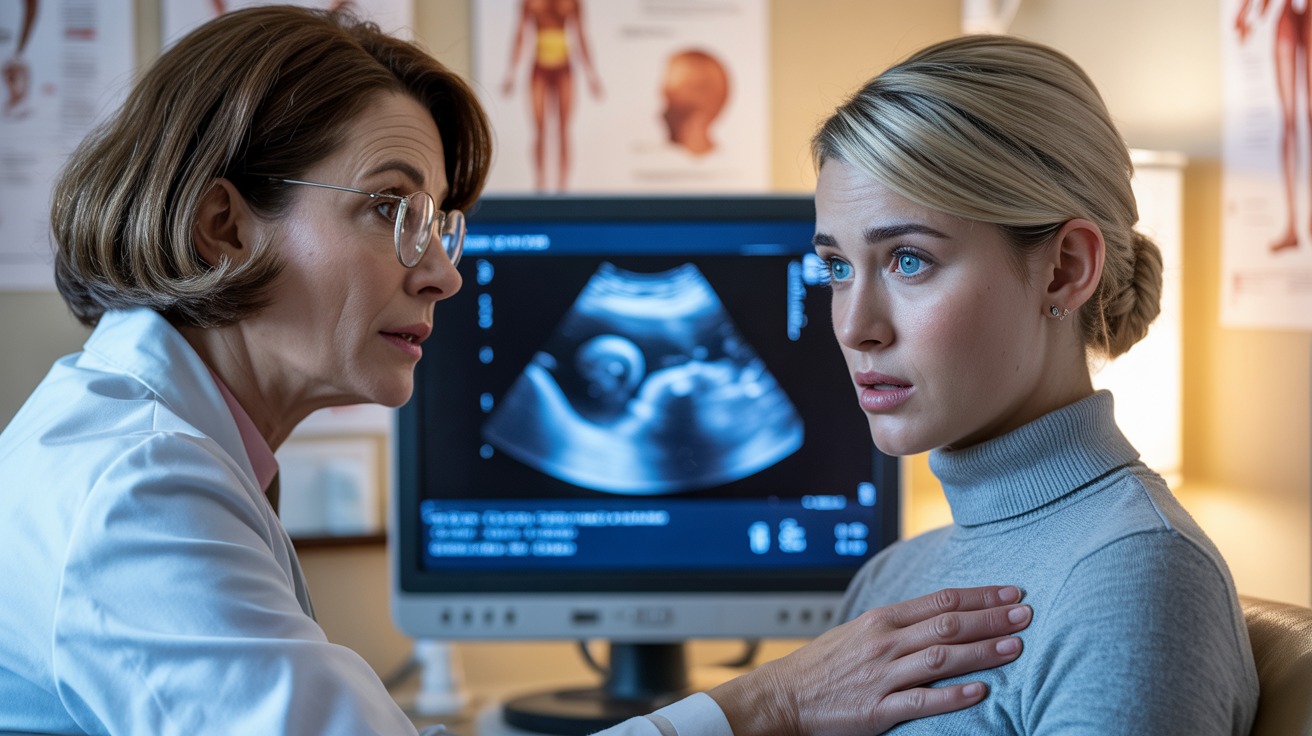

We talked about books, about history, about all the years we had missed. He showed me photos of my grandmother, a woman named Eleanor who had died when I was five.

She had known about me, Theodore said. She had wanted to meet me desperately, but Constantia had refused all contact and Eleanor had died without ever holding her grandchild.

I keep one of those photos on my nightstand now. Sometimes I talk to her late at night when I can’t sleep.

I don’t know if she can hear me, but it helps. Nadia and I are rebuilding our relationship slowly.

She moved back from Europe and started working as a translator for a nonprofit. She visits once a month.

We don’t talk about our parents much; there’s too much pain there, still too raw. But we talk about other things—sister things, future things.

She’s the only Brennan I kept. Jace tried to contact me a few times—texts, emails, even a handwritten letter I threw away without reading.

Eventually, he got the message. Last I heard he was engaged to someone else; good luck to her.

The neighbors think Theodore and I are quite the pair. The retired professor and the accountant living side by side, having Sunday dinners on the porch.

I overheard one of them wondering if we were some kind of eccentric intellectuals. Dangerous criminals, the both of us.

Watch out for the woman with the spreadsheets and the man with the poetry books. We might audit your taxes and then discuss Whitman.

The Brennan house sold eight months after the auction. A young family bought it—a couple with two children and a golden retriever.

I watched the moving trucks from Theodore’s porch and felt something unexpected: peace. Not happiness, exactly, but peace.

One morning, about a year after the trial, I found Theodore sitting on his porch with a cardboard box. He looked different that day—older, somehow, like he had been carrying something heavy for a long time and was finally ready to set it down.

He asked me to sit with him. I did, settling into the chair that had become mine over the past months—the one with the faded cushion that Theodore kept meaning to replace but never did.

I told him not to bother; that cushion had survived longer than my engagement to Jace, which meant it had earned its place. He said he had something for me, something he had been saving for 25 years.

Inside the box were birthday cards—25 of them, one for every year since he had moved across the street. Each card was still sealed in its envelope, my name written in Theodore’s careful handwriting on the front.

I opened them one by one. The card from my seventh birthday described watching me learn to ride a bicycle.

How I had fallen three times, gotten back up each time, and finally pedaled to the end of the street with my arms raised in triumph. He had been celebrating silently from his window.

The card from my 16th birthday mentioned a boy who had come to pick me up for what must have been my first date. Theodore had wanted to be the one standing on that porch protecting his daughter, threatening the boy with vague but meaningful consequences.

Instead, he had watched from behind his curtains. Every card was like that: 25 years of milestones observed from a distance.

My graduation, my first car, my first apartment—he had documented all of it. He had loved me through all of it, even when I didn’t know he existed as anything other than a monster.

The card from my 30th birthday mentioned my engagement to Jace. Theodore had seen the ring when I visited my parents that Christmas.

He had worried that something wasn’t right. The way Jace looked at me—the way people look at investments rather than partners.

He had wanted to say something but knew he couldn’t. So he wrote it in a card I would never receive and hoped I would figure it out on my own.

I did figure it out eventually, just not soon enough. The last card was different.

It wasn’t sealed, and it wasn’t old. Theodore had written it just days before.

“I never stopped believing you would find your way home. And now that you’re here, I want you to know something I’ve waited your whole life to tell you. I am proud of you. Not for what you did to them, but for who you became despite them. You are strong and kind and brave. You are everything I hoped you would be. You are my daughter, and I love you.”

It said.

I cried reading that card. Not the quiet tears I had trained myself to produce over years of family dinners.

Real tears, ugly tears—the kind that come when something inside you finally breaks open and heals at the same time. Theodore held my hand while I cried.

He didn’t say anything; he didn’t need to. Some things are beyond words.

When I finally stopped crying, I looked across the street at the house where I had grown up. The new family had painted the shutters blue.

The children had left bicycles on the lawn. A tire swing hung from the old oak tree, something my parents had never allowed because it would have ruined the aesthetic.

The house looked happy now in a way it never had when I lived there. I thought about Constantia in her prison cell, probably writing letters I would never read.

I thought about Jose doing community service somewhere, certainly complaining the whole time. I thought about Wesley rebuilding his reputation, probably already spinning stories about how he had been manipulated.

They would move on eventually. They would find ways to justify what they had done, to convince themselves they were the real victims.

People like them always did, but I was done thinking about them. I had spent 32 years in their orbit, defining myself by their approval, measuring my worth by their attention.

Now I had something better. I’m not alone anymore.

![[FULL STORY] What’s the worst part about being the “responsible” sibling?](https://en3.spotlight8.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/image_2026-01-13_103613988.png)