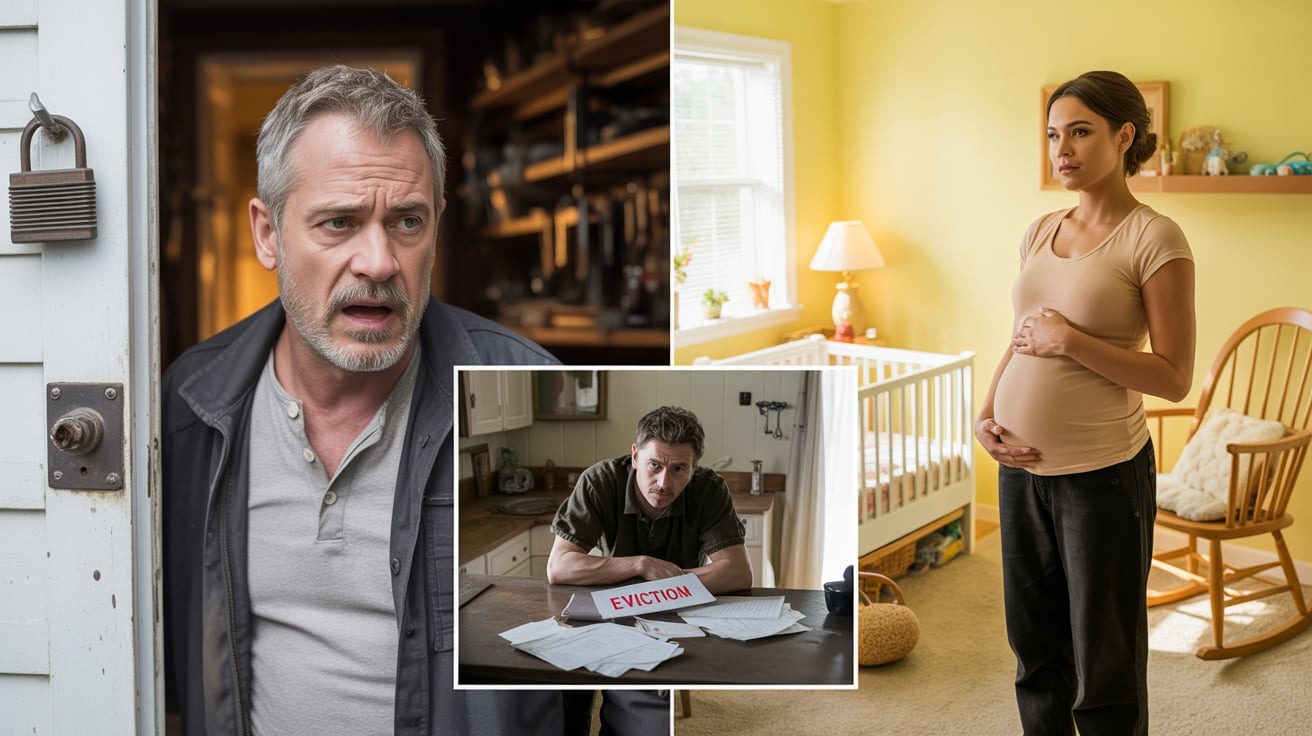

My Family Left Me in the ER Arguing Over the Bill – When My Heart Stopped for the Third Time…

The Cost of a Life

My family left me in the ER arguing over the bill when my heart stopped for the third time. They went out for dinner, then the windows shook under the roar of rotor blades.

My billionaire wife’s helicopter was landing. My name is James Rivera, and the first time my heart stopped, my mother asked if the defibrillator paddles were going to show up on the itemized bill.

The second time it stopped, my father checked his watch and muttered something about valet parking rates. The third time it stopped at 4:37 p.m. on a Tuesday in October, they weren’t even in the room.

They were in the cafeteria arguing over whether the Cobb salad was worth $8. I know this because nurse Rachel told me later, her voice shaking with something between fury and disbelief.

“Your family,” she said, “is the worst I’ve seen in 15 years.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Three weeks before my heart decided to quit on me, I was completely healthy.

I was a 32-year-old marathon runner. I was the kind of guy who meal prepped on Sundays and did yoga on Thursdays.

A Routine Turn Fatal

My wife Elena used to joke that I was annoyingly disciplined about my health. This made the irony of what happened next almost funny—almost.

The appendectomy was supposed to be routine laparoscopic. Dr. Lisa Keading explained it in her office, showing me a diagram on her tablet.

“Three small incisions. You’ll be home the same day, back to running in two weeks.”

Elena was in Geneva finalizing the acquisition of a biotech firm. Volkov Pharmaceuticals was expanding into gene therapy, and she was spending 16-hour days in conference rooms with Swiss regulators and lawyers who billed by the minute.

When I called to tell her about the surgery, she offered to fly home immediately. “It’s appendicitis,” I said, laughing, “not heart surgery. I’ll be fine.”

“You sure? I can have the jet back in six hours.”

“Stay, close your deal. My parents will drive me.”

That was my first mistake. My mother, Diana Rivera, showed up 40 minutes late complaining about traffic on the 405.

My father, Robert, stayed in the car on a conference call about some real estate investment in Scottsdale. My sister Sophia didn’t come at all.

She was filming content for her lifestyle Instagram. “Hospital vibes aren’t really my aesthetic,” she’d texted, followed by three crying-laughing emojis.

The Infection Takes Hold

The surgery went perfectly. Dr. Keading removed my appendix at 7:15 a.m. on a Thursday morning.

By 9:30 a.m., I was in recovery, groggy but stable. I was asking the nurses for ice chips and making jokes about the hospital gown.

By 11 a.m., I was spiking a fever of 102.4. By 2 p.m., my incisions were weeping fluid that smelled wrong—sweet and rotten, like fruit left too long in the sun.

By 6:00 p.m., I couldn’t feel my hands. The infection moved like wildfire through dry brush.

One moment I was fine, cracking jokes with the nursing staff. The next I was drowning in my own body.

“Necrotizing fasciitis,” Dr. Keading said, her face pale under the fluorescent lights. She was standing at the foot of my bed with two other doctors.

Dr. Marcus Webb was the hospital’s infectious disease specialist with 23 years of experience. Dr. Priya Chandra was a surgeon who specialized in septic complications.

Arguing Over the Bill

Dr. Webb was the one who said the words that would haunt me. “Flesh-eating bacteria. We need to operate immediately.”

It was 11:47 p.m. I’d been in the hospital for 16 hours, and my body had gone from healthy to dying in less than a day.

My mother was scrolling through her phone, her manicured nails clicking against the screen. “Another surgery? How much is that going to cost?”

Dr. Chandra blinked, her expression frozen somewhere between professional composure and raw disbelief. “Mrs. Rivera, your son’s life is at risk. The infection is spreading to his abdominal wall without immediate intervention.”

“I heard you the first time,” my mother snapped, not looking up. “I’m asking about cost. We have a high deductible plan—$5,000 deductible—and we’re only at 3200.”

Dr. Keading’s jaw tightened. I could see the muscle jumping under her skin. “We can discuss billing later. Right now—”

“We’ll discuss it now,” my father interrupted, finally looking up from his laptop. He was still in his suit from work, tie loosened, reading glasses perched on his nose.

“We’re not signing anything until we see an estimate.”

I wanted to scream, but screaming required energy I didn’t have. The infection had already claimed that along with my ability to move my left leg and feel anything below my rib cage.

They spent 23 minutes arguing with the hospital’s billing coordinator while I lay there. My abdomen was distending like a balloon and my blood pressure was dropping from 110/70 to 88/54.

My skin was turning the color of old newspaper. Finally, Dr. Webb made the call.

His voice was cold and professional, the kind of tone that brooks no argument. “This is a medical emergency. I’m invoking the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. We’re operating with or without consent.”

My parents threatened to sue, but they signed the papers. The surgery took 4 hours and 18 minutes.

They removed 16 inches of dead tissue from my abdominal wall. They packed the wound with medical-grade gauze soaked in antimicrobial solution and started me on three different IV antibiotics: Vancomycin, Meropenem, and Linezolid.

Organ Failure and Indifference

When I woke up in the ICU at 4:15 a.m., my father was asleep in the chair, snoring softly with his mouth open. My mother wasn’t there.

According to the night nurse, she’d gone home to get proper sleep in a real bed. Day two was worse.

The infection had spread to my bloodstream. “Sepsis,” Dr. Webb explained it to my parents using small words, like he was talking to children who’d never passed basic biology.

“The bacteria is in his blood. His organs are struggling. His kidneys are functioning at 42%, and his liver enzymes are elevated.”

“We’re starting aggressive treatment, but he needs close monitoring.” My mother frowned at her phone. “How long will he be in the ICU?”

“At least a week, possibly longer, if his organ function doesn’t improve.” “A week?”

My father stood up, angry now. “We have plans. We’re supposed to be in Napa this weekend—wine tasting tour. We’ve had these reservations for six months.”

Dr. Webb stared at him. He just stared.

The silence stretched so long I could hear the ventilator in the next room and the beep of someone else’s heart monitor. “Mr. Rivera,” Dr. Webb said slowly, “your son is in multiorgan failure. Do you understand what that means?”

“I understand you’re being dramatic,” my father said. “He’s young, he’s healthy, he’ll bounce back.”

“Sir, his kidneys are failing.” “So give him medicine.”

“We are, but if his kidney function drops below 20%, we’ll need to start dialysis.” My mother looked up sharply. “How much does dialysis cost?”

I closed my eyes. The machines beeped steadily, monitoring a body that was giving up piece by piece.

Through the fog of pain and morphine, I thought about Elena. She’d be in meetings right now, probably wearing one of her sharp black suits and negotiating in three languages.

She would be commanding rooms full of men twice her age. I should have called her and should have told her it was bad.

But I didn’t want to worry her. I didn’t want to pull her away from the deal she’d been working on for eight months.

That was my second mistake. On day three, my kidneys hit 22% function.

Dr. Chandra added a nephrologist to my team, Dr. Alan Foster, who’d been treating renal failure for 19 years. He explained dialysis to my parents while they sat there looking bored, like he was explaining how to use a coffee maker.