My mother-in-law CUT OFF my daughter’s CURLY HAIR to make her “MATCH BETTER”

I posted about the nightmares that evening, careful not to include details that would identify Zoe’s therapist or reveal too much about the therapy process. I explained that my 2-year-old was having nightmares about her grandmother and getting anxious about family events because she’d learned that family gatherings meant watching other kids get love while she got ignored.

The response was immediate and intense. Comments flooded in within the first hour with people expressing anger that a grandmother’s favoritism had traumatized a toddler badly enough to cause nightmares.

Several followers shared the post to their own pages, adding commentary about how grandparent favoritism was a form of child abuse that people didn’t take seriously enough. By the next morning, the account had jumped from 1,000 followers to 5,000.

Local parenting bloggers started reaching out through direct messages asking if they could cover the story. A few small news sites that focused on family issues sent requests for interviews.

The attention was bigger than I’d expected when I first created the account, but it felt right that people were finally taking this seriously. Tom and I talked about the interview requests over coffee while Zoe played in the next room.

Part of me wanted to do a formal interview and really blast Ruth’s behavior into the public eye. But Tom worried “that too much media attention might backfire and make us look like we were just trying to hurt his mother rather than protect our daughter.”

We decided against the formal interviews, but I did write a detailed post explaining the complete history of Ruth’s favoritism. I included specific examples with dates, like Ruth showing up three hours late to the hospital when Zoe was born because of Olivia’s dance recital.

I wrote about the $10 pharmacy stuffed animal for Zoe’s first birthday versus the bounce house and princess impersonator for Olivia’s party the same month. I listed every time Ruth had refused to babysit Zoe while taking Olivia and Chloe every weekend.

I described Ruth’s house covered in professional photos of two granddaughters while Zoe’s picture was hidden behind a grocery list on the fridge. I explained the hair comments, the expensive accessories for the other girls, the Easter dresses.

I ended with Ruth’s own words about wishing we’d given her a blonde granddaughter and her explanation that Zoe’s hair made the other girls look bad in photos. The post was long and detailed, and I hit publish before I could second-guess myself.

Within hours, it had been shared across multiple local parenting groups and community pages. People I’d never met were commenting “that they’d seen Ruth around town and always thought she seemed like such a nice grandmother.”

Others said they’d witnessed some of these incidents at family gatherings or community events and hadn’t realized how bad the full pattern was. The post went viral within our local community, spreading through neighborhood groups and school parent organizations.

People started recognizing Ruth at the grocery store and the pharmacy. Hank called Tom two days after that detailed post went up.

He was mad, his voice loud enough that I could hear him from across the room even though Tom didn’t have him on speaker. He said “someone had confronted Ruth at the pharmacy asking her directly if she was the grandmother who’d cut off her granddaughter’s hair out of favoritism.”

Ruth had apparently broken down crying right there in the pharmacy aisle and come home so upset she couldn’t stop shaking. Hank wanted to know “how he could be okay with strangers harassing his mother in public over family business.”

Tom let his brother rant for a minute before responding in this calm, cold voice that I’d never heard him use before. He told Hank “that public shame was a natural consequence of Ruth’s actions.”

He said “maybe their mother should have thought about her reputation in the community before she cut off a toddler’s hair because it didn’t match her favorite granddaughters.”

He pointed out that Ruth had spent two years publicly favoring Olivia and Chloe at family events and gatherings where other people could see, so she’d already made her behavior public long before I posted about it. Hank tried to argue “that what happened in the family should stay in the family.”

Tom asked him “when exactly the family had planned to address Ruth’s treatment of Zoe if we’d kept quiet.”

Hank didn’t have an answer for that. Camila reached out the next day asking if we could meet for coffee without the kids.

I almost said no because I was tired of family members wanting to process their feelings about Ruth’s behavior while my daughter was in therapy dealing with the actual damage. But Camila had been the only one to really apologize, so I agreed to meet her at a coffee shop near my house.

She was already there when I arrived, sitting at a corner table looking like she hadn’t slept well. When I sat down, she started crying before I could even order my coffee.

She talked about all the times she’d accepted her mother’s favoritism as normal. She admitted “she’d felt proud that Olivia was Ruth’s favorite and never questioned why that meant Zoe had to be excluded.”

She admitted she’d felt superior having the favorite grandchild, like it meant she was doing something right as a parent that Tom and I weren’t. She said “she’d convinced herself that Ruth’s constant praise and expensive gifts for Olivia were just because they had a special bond not because Ruth had a problem with Zoe’s appearance.”

Camila cried harder when she talked about the hair, saying she kept thinking about how Zoe must have felt sitting there watching Ruth cut away her curls. She said “she’d been looking back through photos from family events and could see Zoe’s face in the background of pictures always watching Olivia and Chloe get attention while she sat alone.”

She asked me “how she could have missed something so obvious for so long.”

I appreciated that she was being honest, but told her that seeing the problem now didn’t fix the two years Zoe spent watching Olivia get everything while she got nothing. Camila nodded and wiped her eyes with a napkin that was already soaked through.

She said she wanted to make changes in how she handled Ruth’s gifts and attention toward Olivia, but didn’t know where to start. Tom had joined us by then because I’d texted him to come.

He suggested “Camila could start by turning down Ruth’s excessive gifts and experiences for Olivia or at least insisting that Ruth include all three granddaughters equally.”

Camila looked down at her coffee cup and admitted this felt hard because Olivia had gotten used to being spoiled by Ruth. She said “Olivia expected special treatment now and would be upset if the shopping trips and expensive presents stopped.”

Tom pointed out that was exactly the problem. He said “Ruth had taught Olivia to expect favoritism and now it was affecting how she treated her cousins.”

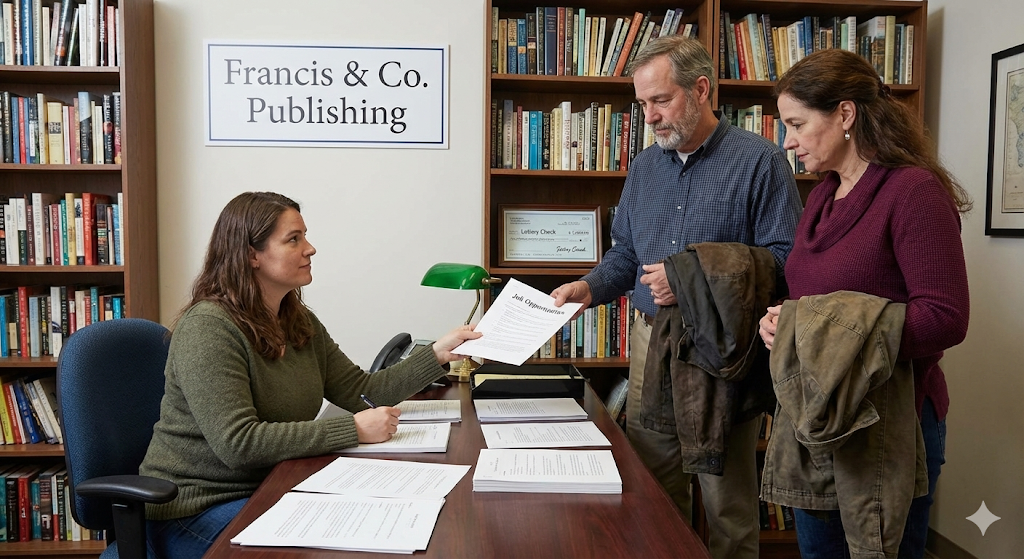

Camila agreed it was necessary even though she didn’t know how to explain it to a six-year-old. The next day I got a message through the Grandmas Who Play Favorites account from someone who said she was a family therapist specializing in favoritism dynamics.

She offered to do a phone consultation with me for free because my post had resonated with her professional experience. We set up a call for that afternoon and she explained that grandparent favoritism often came from prejudice about appearance, personality, or circumstances.

She said it rarely changed without serious intervention because the grandparent usually didn’t see their preference as a problem. I asked “if there was any hope for Ruth to change” and the therapist was honest that most grandparents who showed this level of favoritism didn’t develop genuine insight.

She explained they might modify their behavior when forced to, but the underlying preference usually remained. She said they just got better at hiding it or found more subtle ways to show favoritism.

The conversation lasted almost an hour and she gave me specific examples of patterns she’d seen in other families. I shared the therapist’s insights on the social media account without identifying her.

Hundreds of people commented saying this matched their experience with favoritist grandparents. Many adult children shared that they eventually cut off contact entirely because the dynamic never truly improved.

One woman wrote that her mother still favored her brother’s kids twenty years later and had missed her daughter’s wedding because it conflicted with her favorite grandchild’s soccer game. Another person shared that their father had left money to only two of his five grandchildren in his will because those were the ones who looked like him.

The comments kept coming for days and each one made me more certain that protecting Zoe from Ruth was the right choice. Three weeks after the hair incident, a thick envelope arrived at our house with Ruth’s return address.

Tom brought it inside looking like he wanted to throw it away without opening it, but I took it from him. The letter was three pages long, written in Ruth’s careful handwriting.

Most of it focused on how hurt she was by the social media posts and how we’d ruined her reputation in the community. She wrote about people whispering about her at church and her book club friends asking uncomfortable questions.

She said she couldn’t go to the grocery store without feeling like everyone was staring and judging her. The letter included one paragraph about regretting the haircut, buried in the middle of page two.

She wrote “that she wished she’d asked permission first” but never actually apologized for the years of favoritism or acknowledged that she’d treated Zoe as less important than her other granddaughters.